Is it possible to build a full EchoLink® node using a $4 microcontroller? I'm not completely sure, but let's find out. The goal of this project is to create the smallest, cheapest way to put a radio onto the EchoLink network. If you are new to the world of EchoLink please see the official website for complete information. EchoLink is a peer-to-peer VoIP (voice over IP) network used to link amateur radio stations across the Internet.

There are much easier ways to get onto EchoLink. The MicroLink project will only be interesting to someone who wants to get deep into the nuts-and-bolts of EchoLink/VoIP technology. In fact, you should start to question the sanity of anyone who spends this much time building their own EchoLink station. I am a homebrew enthusiast and I try to avoid off-the-shelf software/components where possible. This has been a huge learning opportunity.

The system currently runs on a Pi Pico (RP2040) development board. I'm pretty sure it could also run on an ESP-32, or possibly an Arduino of the correct caliber. More experimentation is needed here.

Here's the current demo video:

The microphone/analog section still needs a lot of work.

Here's what it sounds like over the air:

The official PC-based EchoLink client written by Jonathan Taylor (K1RFD) is excellent and is the quickest/easiest way to get on EchoLink. Download it here. There are also versions that run on mobile phones. MicroLink is not a supported part of the EchoLink family of products.

I've learned many things about EchoLink during this project. One thing is for sure: Jonathan (K1RFD) who created the EchoLink system is an outstanding engineer and we should all be greatly appreciative of the work that he and the rest of the EchoLink team do on behalf of the amateur radio community.

I am good in QRZ at KC1FSZ if you have any questions or suggestions.

My goal was to build a complete station from scratch, with no strings attached to PCs/servers.

Once things are working smoothly I will integrate this onto a single PCB for ease of use with radios (link mode) and/or direct integration with repeaters.

This project required an in-depth examination of how the EchoLink protocol works. The notes I created during this analysis are located here.

The hardware is used in two configurations:

- A client, with microphone and speaker for connecting to EchoLink conferences, links, and repeaters.

- A link station, with integration to a radio to allow remote access.

- The main processor is a Pi Pico (RP2040) development board. $4.00 on DigiKey.

- Internet connectivity currently comes over WIFI using an ESP-32-WROOM development board. $5.00 on Amazon. Work is underway to provide a 4G cellular data option using a SIM7600 module. More on this to follow.

- The microphone is an electret condenser with a LVM321 pre-amp and low-pass anti-aliasing filter. The microphone part needs work. The next revision will use a TLV9161 op amp for the microphone pre-amp to reduce noise.

- Audio input sampling uses the integrated ADC in the RP2040.

- Audio output generation uses the MicroChip MCP4725 I2C digital-to-analog converter. $1.27 on DigiKey.

- Audio amplification uses the LM4862M 825mW amplifier. $2.23 on DigiKey.

- The local T/R key is from Federal Telephone and Telegraph Company (Buffalo, NY), made in 1920. Priceless.

- Isolation transformers and optocouplers are used to eliminate the need for common ground between the radio and the MicroLink system. This helps to reduce digital noise.

- The radio link is a Baofeng BF-F8HP.

- The main station firmware is completely homebrew (C++, see GitHub repo).

- The ESP-32 runs the Espressif AT firmware (version 3.2.0.0).

- Importantly, audio compression/decompression uses a GSM 06-10 Full Rate CODEC which is homebrew in C++. Getting that to work required studying the European Telecommunications Standards Institute specification for GSM and a lot of testing, but this was extremely interesting.

- I'm not using the Arduino development environment for this project. The toolchain is CMake/GCC/GDB using the Pico SDK. I like this environment a lot. The firmware is flashed via SWD using openocd.

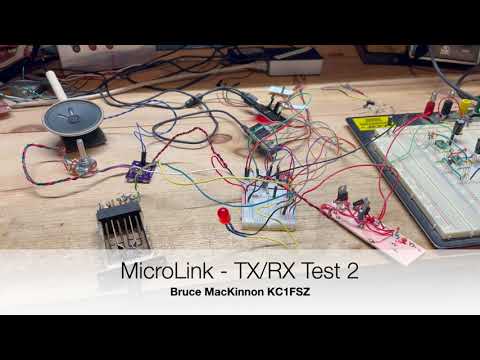

Here's a picture of the parts on the bench so you can tell what you're looking at.

MicroLink identifies itself using a version string of 0.02MLZ.

Microphone Pre-Amp

Performance audio circuits are not my forte. The quality is improving with each iteration. This is what I built originally, but a new version using parts with better noise specs is in the works.

The microphone part will not be used when the radio is integrated. I will probably leave the speaker/amplifier in for monitoring purposes.

Audio Input

This repeats some of the circuit shown above (minus the microphone gain). This also shows the circuit used for carrier detect (COS). The idea is to boost up the rig's audio output (U6) and then compare it to an adjustable threshold (U8). There is no debounce in the analog part of the COS circuit - that is all done in software.

Audio Output

The main reasons I used the ESP-32 for WIFI connectivity is the fact that the ESP AT command set is very similar to the one supported by the SIM7600 4G cellular module. I am currently working on a version of the MicroLink system that uses 4G internet connectivity.

- The standard audio sample rate for GSM-FR/EchoLink is 8 kHz at 12-bits of resolution.

- The audio CODEC creates/consumes one 640 byte packet every 80ms. One of these packets is moved 12.5 times per second.

- It takes the RP2040 about 7ms to decode a 4x160 byte GSM frame.

- It takes the RP2040 about 30ms to encode a 4x160 byte GSM frame.

- The UDP data rate needed to sustain audio quality is approximately 14,000 baud.

- The RP2040 runs at 125 MHz. Only one of the two processors is used at this time.

- The DAC runs on an I2C bus running at 400 kHz.

- The ESP-32 is on a serial port that runs at 115,200 baud.

- The voice prompts (all letters, numbers, and a few words) take up about 40K of flash. The audio is stored in GSM full-rate format for efficiency.

This is the most comprehensive demonstration that targets the RP2040. This is the code shown in the video demonstration.

At the moment this uses a serial console to take commands and display status.

The test build for the -L station.

At the moment this uses a serial console to take commands and display status.

Runs on a Windows desktop, used for testing purposes only. No TX at this time.

- Set environment variables EL_CALLSIGN, EL_PASSWORD, EL_FULLNAME, EL_LOCATION.

I implemented my audio compression/decompression CODEC for the GSM 0610 Full Rate protocol by following the specification here. The coding scheme is the so-called Regular Pulse Excitation - Long Term prediction - Linear Predictive Coder, generally referred to as "RPE-LTP." This standard was developed as part of the modernization of the European mobile phone system in the late 1990s and is a good balance between efficiency, quality, and compactness.

The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) publishes a comprehensive set of test vectors containing known audio streams (PCM) and the corresponding GSM encoding. I have used that test data to validate that my CODEC is 100% complaint.

The smallest/cheapest microcontrollers lack hardware support for floating-point, so I built my CODEC using fixed point (Q15) math. This was my first major foray into fixed-point DSP.

One of the most difficult challenges I had with this project was getting audio that was "smooth" in both directions. This stuff is probably obvious to people who are well versed in the state-of-the-art of VoIP, but it's all new to me. Here are a few points that will help anyone getting into this.

- Accurate/consistent clocking of the audio chain is essential. GSM uses an 8 kHz clock, which means we need an audio sample once every 125 microseconds. I know this seems hard to believe, but inconsistencies in this clock can be "heard." This is where hardware timers with efficient interrupt service architectures are important. The highest priority activity of the microcontroller should be the creation/consumption of an audio sample every 125 uS exactly - everything else in the system has some leeway.

- An EchoLink receiver gets an audio packet approximately every 80 ms. Each packet contains 4 frames that each represent exactly 20 ms of audio. Finally, each frame contains 160 samples which each represent exactly 125 uS of audio. From point #1 above, we already know that the timing of the 160 samples within each frame is critical. However, we also need ensure that the 20 ms frames are played continuously without the slightest gap between them. This gets into an interesting problem because the frames are streaming across the busy internet (not to mention low-cost WIFI hardware) and may be subject to small timing inconsistencies. There is simply no way to ensure that an EchoLink packet will arrive every 80 ms. Sometimes the gap might be 81 ms, sometimes 79 ms, etc. This variability is known as "jitter" and it is a common issue in VoIP systems. The fix is simple: we need to delay/buffer the audio generation in the receiver slightly to give ourselves a margin of error to accumulate packets. The MicroLink system keeps a buffer of 16 audio packets and holds back the start of audio generation (after squelch break) until the buffer is half full. This means that the receive path is delayed by around 8 x 80 ms above and beyond any delay in the Internet itself. Experimental work is ongoing to make this adaptive so that the delay is minimized. Of course if the buffer empties out (i.e. several slow packets in a row), all bets are off.

Two important things that make a difference for audio noise performance. Note that these comments are relevant when using the Pi Pico board as-is. The rules will be different if using the RP2040 chip directly.

Per Pico datasheet:

For much improved ADC performance, an external 3.0V shunt reference, such as LM4040, can be connected from the ADC_VREF pin to ground. Note that if doing this the ADC range is limited to 0-3.0V signals (rather than 0-3.3V), and the shunt reference will draw continuous current through the 200Ω filter resistor (3.3V-3.0V)/200 = ~1.5mA.

Per Pico datasheet:

AGND is the ground reference for GPIO26-29, there is a separate analog ground plane running under these signals and terminating at this pin. If the ADC is not used or ADC performance is not critical, this pin can be connected to digital ground.

(These notes are not comprehensive yet.)

git clone https://github.com/brucemack/microlink.git

cd microlink

git submodule update --remote

mkdir build

cd build

cmake ..

make <target>

(These notes are not comprehensive yet.)

git clone https://github.com/brucemack/microlink.git

cd microlink

git submodule update --remote

mkdir build

cd build

cmake -DTARGET_GROUP=pico ..

make <target>

esptool.py --chip auto --port /dev/ttyUSB0 --baud 115200 --before default_reset --after hard_reset write_flash -z --flash_mode dio --flash_freq 40m --flash_size 4MB 0x0 /home/bruce/Downloads/ESP32-WROOM-32-V3.2.0.0/factory/factory_WROOM-32.bin

# Used to receive UDP packets

netcat -u -l 5198

# Used to send UDP packets. The printf command supports non-printable.

printf 'Hello\rWorld' | nc -u -w1 192.168.8.210 5198

# Login test

printf "lKC1FSZ\254\254xxx\rONLINE0.02MLZ(08:11)\rWellesley, MA USA\r" | nc -w 10 naeast.echolink.org 5200

- 3.5mm Jack

- Tip - NC

- Ring - Rig mic in, MicroLink audio out

- Sleeve - PTT when pulled to ground

- 2.5mm Jack

- Tip - Rig speaker+ out, MicroLink audio in

- Ring - Rig ground

- Sleeve - Rig ground

This has been discussed at length in other venues. The method of detecting the receive carrier depends on the radio you are using. Unless you are willing to crack it open, there is no explicit carrier detect "signal" on the Baofeng HT. My integration with this rig just listens for noise on the audio output line and triggers accordingly. That seems to work just fine. See the schematic for details.

- Official EchoLink Site: https://www.echolink.org/

- Pi PICO Stuff

- ESP-32

- SIM7600 Cellular

- SIM7600 module AT Command Reference: https://www.waveshare.net/w/upload/6/68/SIM7500_SIM7600_Series_AT_Command_Manual_V2.00.pdf

- SIM7600 module application notes: https://www.waveshare.com/w/upload/4/4b/A7600_Series_TCPIP_Applicati0n_Note_V1.00.pdf

- Windows Audio Related:

- Components

- Rig Integration

- Analog/Audio

- Other

- Analog Devices Filter Wizard

- https://www.purevpn.com/what-is-vpn/protocols/openvpn

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OpenVPN

- https://www.analog.com/media/en/technical-documentation/application-notes/an-1368.pdf

- Information about Ferite Beads from Altium.

- MD5 Implementation: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~jcl/linux/seal/md5.c